Edible Mushrooms

Food, medicine, compost, soil improvement, bioremediation...mushrooms have so much to offer the homesteader, backyard gardener or even basement dweller.

I am just beginning my relationship with mushrooms on the homestead. But because I see so much potential in mushrooms I want to point out their utility and versatility to my readership. Where I live, hunting for morel mushrooms in the woods is a popular spring activity. Growing up, my family and I would occasionally go looking for morels and occasionally find some. Then back when I was in college I took a mycology class (study of fungi). This opened my eyes to the many attributes that mushrooms have to offer.

I had the privilege to learn from the esteemed mycologist Dr. Orson Miller who authored multiple books on mushroom identification and has seven species of fungi named in his honor. In addition to classroom lectures, he guided our class on walks through the woods near our college campus where we would search for mushrooms, both edible and inedible. We would then bring our specimens back to the lab to do spore prints and make slides with mushroom spores for definitive identification under the microscope. Once after a large harvest of Chicken of the Woods his wife Hope Miller, who had written a mushroom cookbook, came in and prepared a delicious mushroom feast for us.

I remained fascinated with mushrooms over the years. Unlike plants, mushrooms don’t require light to grow (although as you’ll see later there are nutritional benefits to growing mushrooms in sunlight). So if you live in an apartment, or even a dark basement, you could still grow mushrooms. Once when I was living in a town house without a yard I bought an indoor Lion’s Mane mushroom kit in a bag and grew out Lion’s Mane mushrooms. But I didn’t do much more with mushrooms until I settled onto a homestead.

I’ll admit I’ve had more failures than successes. I have tried making mushroom logs a couple of times to no avail. I suspect they dried out. One year I tried planting King Oyster mushrooms in a bed of wood chips in a corner of the garden but they never came up. I’m not sure why.

Then this past year I planted Wine Cap (Stropharia rugosoannulata) mushrooms in a designated patch of my garden and was rewarded with a bountiful crop. Last year’s wet summer was an ideal opportunity to establish a bed of mushrooms. The Wine Caps came in flushes from late summer till well after the first frost. Some of the mushrooms got damaged by frost but more would come up during periods of milder weather, particularly wet weather. If I knew a frost was coming and I had time, I’d cover the emerging mushroom buttons with some wood chips or straw. It wasn’t until the hard freezes of late fall/ early winter that the Wine Cap bed finally stopped producing.

In terms of flavor, I consider Wine Caps comparable to commercially available button mushrooms. They were delicious sauteed, on pizza and in soups. I ate a lot of mushroom soup last year. And I had so many more mushrooms than I could eat fresh that I chopped up and dehydrated most of them for future use.

One thing I really appreciate about Wine Cap mushrooms is that they can be grown in and amongst other crops in the garden. Reportedly, they will return to a garden even after being plowed under so long as they are given more substrate to grow on. Of course, that substrate must be kept moist. Their preferred substrates are straw and/ or wood chips.

I read that Wine Caps would grow faster in straw but longer in a bed of wood chips. So I made lasagna layers of straw and fresh hardwood chips (on top of a base of wetted cardboard to suppress weeds). I got the fresh hardwood chips from a local landscaper who was just happy to find a place to dump them. I sprinkled the mushroom spawn between the layers, making sure it all got covered with wood chips as the top layer. I then watered the bed thoroughly. I had a lot of help from rainy weather but continued watering the bed during the occasional dry spell.

Shortly after I set up the Wine Cap bed I made separate beds of Oyster and Nameko mushrooms. Those have yet to produce. I’m hopeful I’ll see some Oyster mushrooms this spring. I don’t expect to see Namekos until next winter (assuming they come up at all).

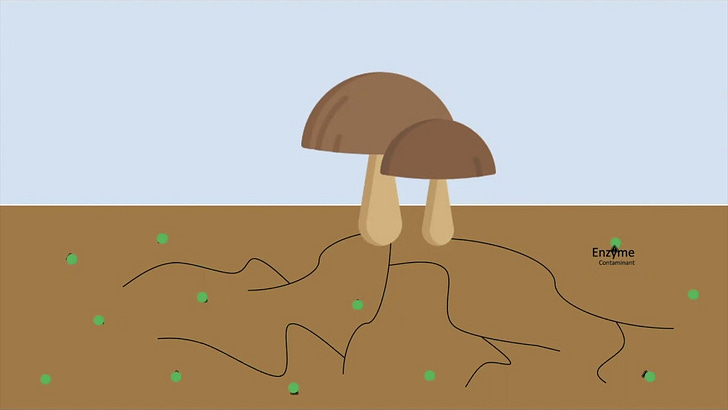

Most cultivated mushrooms must be grown from a tissue culture of mushroom mycelium that has been established in a sterile substrate (i.e. mushroom food) under laboratory conditions. Mycelium is the thin, filamentous web of “roots” from which mushrooms grow. Mycelia is the pleural form of mycelium. The mushrooms you pick are the comparatively small fruiting bodies extending to the surface from the vast network of mycelium growing out of sight in whatever log, manure or decaying plant matter the mushrooms are feeding on.

Molds are another form of fungi. Their spores are ubiquitous in the air and surrounding environment. So without sterile laboratory conditions, including a laminar flow hood, the substrate in which the mushroom spawn is grown would easily be contaminated with mold. The average person interested in growing mushrooms probably isn’t going to want to invest in all the equipment, space and skills needed to perpetuate their own mushroom tissue cultures and spawn (although some people do eventually take it to this level).

Most people who want to grow mushrooms start out by buying commercially produced spawn. If you are buying mushroom spawn in order to grow mushrooms you will be faced with various options. If the substrate is sawdust it is known as sawdust spawn. If it is grain it is known as grain spawn. Sawdust or grain spawn is typically used for starting mushroom beds (such as those made with wood chips, straw, etc.). However, commercial mushroom growers will sometimes use specialized equipment to inject sawdust spawn into logs. But the most common technique for inoculating mushroom logs is with wooden dowels colonized with mushroom mycelia. These dowels are generally known as plug spawn. The wooden pegs are designed to be driven into holes drilled in logs that have been freshly harvested and cut for mushroom cultivation.

The substrate a mushroom ultimately grows on could be a log, stump, wood chips, sawdust, straw, compost etc. While large scale commercial operations may sterilize their mushroom grow media, this isn’t generally necessary for most species grown by the small scale grower. So if you’re starting a mushroom bed with wood chips or straw, for instance, you don’t usually need to first sterilize the wood chips, logs or straw (with certain exceptions).

However, the straw you use for growing mushrooms should at least be clean (i.e. not a moldy bale of straw that’s been left outside). If you’re making a mushroom bed with wood chips they should generally be fresh wood chips. Likewise, logs used for mushroom cultivation should be relatively fresh and not colonized with other fungi before being inoculated with mushroom plug spawn.

There are exceptions to this rule of thumb with some species of edible mushrooms growing best as secondary colonizers of wood that has already been partially decomposed by other fungal species (but this is the exception rather than the rule). So be sure to read up on the specific requirements of the particular species you are trying to grow.

If you have no outdoor space to grow mushrooms, you want mushrooms fast or you are overwhelmed with all the variables involved in outdoor mushroom cultivation, the simplest, fastest way to grow mushrooms is to order an indoor mushroom kit. This is basically a bag of sawdust spawn inoculated with mycelia. But instead of opening up the bag and scattering it over a bed of wood chips or straw (or whatever its preferred substrate may be) you simply cut slits in the sides of the bag for mushrooms to grow out of.

The mushroom bag must be kept moist with mistings of water from a spray bottle and should be stored in some sort of lidded plastic box (or perhaps a trash bag) to lock in the humidity until the mushrooms emerge. Usually these kits will produce within days to weeks, rather than waiting weeks to months (even over a year in some cases) for a mushroom bed or log to produce. The disadvantage of this approach is you get far lower yield from the bag of substrate than if you had given the mushrooms more food to grow on by spreading them in a bed of more substrate or inoculating them into logs. The mushroom kit will also produce over a much shorter period of time than a mushroom bed or logs. That’s because the mushrooms in the kit have a very limited food supply.

Most people use these commercially available mushroom kits as a stepping stone into the world of mushroom cultivation. If they get excited about growing mushrooms from a kit, they may then venture into making mushroom beds or logs. Still, if you have no outdoor space and you wanted to get serious about growing mushrooms in an apartment or a basement, you could invest in the equipment and learn to perpetuate your own mushroom tissue cultures, then grow them out from bags of sterilized substrate indefinitely. Some people will set up shelving units contained in what is essentially a mini green house inside their home just for growing mushrooms. You can do this with plants too but unlike plants mushrooms need no light to grow.

Where space is limited, another option for growing mushrooms would be to inoculate a water saturated straw bale with a species of mushroom that grows on straw. Oyster mushrooms are commonly grown this way. This project could be a bit much for inside a home but in theory you could do this on an apartment balcony or in a garage. If a full-sized straw bale is too unwieldy for you, keep in mind there is a specialty market for mini straw bales, particularly for decorative use in the fall.

While some species of mushroom will grow on straw, other species will only grow on logs from certain species of trees. For instance, the word Shiitake is Japanese for “shii mushroom”. The shii tree is a species of hardwood tree that grows in Japan and is related to oak trees. Thus Shiitake mushrooms became known as the mushrooms that grow on the shii tree. Here in the US, shiitakes are traditionally grown on oak logs.

Other varieties of mushroom will grow in wood chips, sawdust, shredded leaves, corn cobs, grain, paper products such as cardboard or other substrates. Most species of edible mushrooms that will grow on wood chips require hardwood chips, not chips made from conifers (i.e. pine and related species). Whatever substrate you use to grow mushrooms, it must be thoroughly watered initially and kept damp to allow mushrooms to grow. In some cases the substrate may be covered with a tarp to trap in moisture. Large scale commercial Agaricus bisporus mushrooms (the ubiquitous “button” mushrooms found in any grocery store) are typically grown in controlled indoor environments on beds of composted manure.

In contrast to the controlled indoor environment of a large scale commercial Agaricus farm, back yard mushroom cultivation opens up opportunities for creativity, resourcefulness and even playful whimsy. Here is a link to a webpage containing a short video which demonstrates the preparation of cleverly hidden beds of Wine Cap mushrooms among other edible landscape plants. Blogger Albopepper has elevated the art of guerrilla gardening to such a degree as to avoid even the scrutiny of HOA busybodies: https://albopepper.com/wine-cap-mushroom-bed-cultivation-stropharia-rugosoannulata.php

Mushrooms are a relatively low calorie food. They do contain some protein, though not nearly as much as meat or beans. Having said that, mushrooms have a savory flavor and a texture that makes them a popular substitute for meat in many dishes. Nutritionally, where mushrooms really shine is their content of vitamins, minerals and other micronutrients. They tend to be high in B vitamins, potassium, calcium, iron and phosphorous. They also contain carotenoids, polyphenols, indoles and polysaccharides known for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

Interestingly, mushrooms grown outdoors in sunlight are one of a small number of significant dietary sources of Vitamin D found in nature. The same cannot be said of mushrooms grown in the dark. That’s because mushrooms contain ergosterol, a precursor to Vitamin D2. In the presence of UV light the ergosterol molecule is converted to ergocalciferol which is Vitamin D2. This conversion process can happen even after the mushroom has been harvested. Thus drying mushrooms in sunlight increases their Vitamin D content.

According to an article from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, wild harvested morel and chanterelle mushrooms contain a whopping 1200 IU of Vitamin D per 3.5 ounce serving. By contrast, a serving of commercial white button mushrooms grown in the dark contains less than 40 IU of Vitamin D.

A lot of people think of milk and dairy as a source of Vitamin D, but that’s only the case if Vitamin D has been added to the milk. This has been common practice for many years in commercial dairy products in order to prevent Ricketts (i.e. skeletal deformities due to Vitamin D deficiency). But if you were to milk a cow yourself, or perhaps buy milk from a small, local dairy that doesn’t add Vitamin D, that milk would not be a significant source of dietary Vitamin D.

Other dietary sources of Vitamin D include egg yolks and oily fish (i.e. ocean fish). Cod liver oil is a particularly rich source of Vitamin D. Unfortunately, freshwater fish species are not a significant source of Vitamin D. Considering how important Vitamin D is to the optimal functioning of the immune system you may want to consider fresh or dried mushrooms that were grown and/ or dried in sunlight as a way to get more Vitamin D in your diet. This is especially true during the winter when you are getting less Vitamin D through sunlight exposure on your skin.

Of note, all mushrooms contain varying degrees of a carcinogenic compound called agaritine. This includes the raw mushrooms commonly featured in salad bars. Fortunately, this compound is greatly diminished by cooking. It also breaks down with dehydration (though not freeze-drying) and prolonged storage. For this reason, I was warned by my mycology professor never to eat raw mushrooms and I have avoided raw mushrooms ever since. On the other hand, mushrooms also contain anti-cancer compounds. Whether you feel it’s worth it to you to eat raw mushrooms is up to you but I see no point in taking the risk when it is much reduced by cooking.

There are many health benefits associated with mushrooms. Some of this has to do with their nutritional value. But traditionally, certain species of mushrooms have been used for their medicinal properties. The Reishi mushroom is perhaps best known for its medicinal use and has long been used in Chinese herbal medicine. Reishi mushrooms are dense and woody. Therefore they are not eaten but are commonly made into medicinal teas and tinctures.

The following is an excerpt from an overview of the medicinal properties of Reishi mushrooms (Ganoderma lucidum) entitled “Antitumour, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Antiacetylcholinesterase Effect of Ganoderma Lucidum Terpenoids and Polysaccharides: A Review” from the journal Molecules: “G. lucidum contains various compounds with a high grade of biological activty, which increase the immunity and show antitumour, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity.” (Cor et al 2018)

Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor) mushroom is too thin and leathery to serve as a food source but it has long been valued for its medicinal properties. It is known to activate white blood cells which are responsible for fighting infections and cancer.

A number of other mushrooms are also known for medicinal use. It’s beyond the scope of this article to cover all of them. But I want to at least bring this potential use for certain species of mushrooms to your attention.

This seems like a good place to remind you never to consume a mushroom unless you are absolutely 100% certain of its identity. Some mushroom species are readily identifiable based on key features. Others have ambiguous features and can only be positively identified, even by an expert, based on spore prints and/ or microscopy. Some edible mushrooms have poisonous look-alikes. Every year people die of eating poisonous mushrooms they mistook for edible ones. So you had better know what you are doing when it comes to mushrooms. There’s an old Hungarian proverb that says “Every mushroom is edible…once.”

Having said that, mushrooms have a lot to offer culinarily, medicinally and for their contributions to other forms of agriculture. Mushrooms help break down dead plant matter such as straw, wood chips and other agricultural and forestry byproducts into a humus-like soil amendment. Certain species of edible mushroom have a preference for growing on finished compost. Others can be grown on a pile of plant matter that you want to compost. In the latter case, the mushroom mycelia will penetrate the compost pile and help break it down.

If you’ve read my post on Off-Grid Human Waste Management you may be thinking of compost piles in terms of human waste management. I’m not advocating growing edible mushrooms on top of a humanure compost pile, at least not until it has been composted long enough and under the proper conditions to deactivate any pathogens. Mushrooms have an amazing capacity to break down organic matter and some species are even capable of killing pathogens. However, just like you wouldn’t irrigate a crop field with water contaminated with raw sewage, you wouldn’t want to eat mushrooms that may have come into contact with fresh, uncomposted human excrement.

Now if you had a humanure compost pile that had been sitting without further additions for a year while meeting the proper moisture, temperature and other composting requirements, at that point you could grow mushrooms on top of it. If you wanted to grow edible mushrooms on top of such a pile, you could add one or more layers of fresh straw and/ or wood chips (depending on the preferences of the mushroom species) to the top of the pile along with mushroom spawn and plenty of water. Then wait. Mushrooms don’t come up immediately like you may be accustomed to with garden seeds. It could be weeks or even many months before the first crop of mushrooms appears.

The ability of mushrooms to turn plant matter into compost or similar soil amendments is one of their primary contributions to the homestead. But their benefits to plants run even deeper. Certain species of mushrooms actually form symbiotic relationships with plants. This is similar to the concept of “companion planting” where certain crops planted together have mutually beneficial effects on each other.

The Wine Cap mushrooms are particularly suitable for “companion plantings” in gardens. These mushrooms were traditionally grown among grain fields, particularly corn. This species is known for its tolerance of soil disturbance (i.e. plowing a field) which is the only edible mushroom I know of that can take that kind of abuse. In fact, from what I’ve read, Stropharia can be grown almost indefinitely so long as it is provided with fresh substrate (i.e. straw and/ or wood chips). Reportedly, a shovel full of substrate containing Stropharia mycellium can be transplanted to another field to start a new mushroom colony. I have yet to test this out myself. But if true, this is a rare quality in the world of cultivated mushrooms since most mushroom beds peter out after a few years and have to be replenished with fresh commercial spawn.

Another selling point for Stropharia is their ability to improve the soil where they grow. A 2018 study published in the on-line mega journal PeerJ showed an increase in organic matter and bioavailable phosphorus in the soil following the introduction of Wine Cap mushrooms: “Cultivation regimes of Stropharia on forestland resulted in consistent increases of soil organic matter (OM) and available phosphorus (AP) content.” (Gong et al 2018)

Phosphorous is a critical macronutrient for plant growth and one component of commercial N-P-K (Nitrogen-Phosphorous-Potassium) fertilizer. Interestingly, corn is a heavy feeder of phosphorous and phosphorous is second in importance only to nitrogen for corn yields. So perhaps Stropharia’s ability to increase available phosphorous explains why it was traditionally grown in cornfields.

According to the article, “Farmers of Fungi: Growing Mushrooms and Mycorrhizae in Your Vegetable Patch” by Dustin Eirdosh of homestead.org, the Elm Oyster (which is a different species from the common Oyster mushroom) has a beneficial effect on brassica plant species. The brassicas include kale, broccoli, cabbage and brussel sprouts.

“This species also has reported beneficial symbiotic relationships with certain vegetable crops—especially brassica species, and grows exceedingly well among kale and broccoli plants. Paul Stamets has reported a 2-fold increase in brassica yields and a 3-fold total food production increase when the vegetables were grown in the same bed as elm oyster mushrooms.”

Yet another remarkable benefit of growing mushrooms is the ability of certain mushroom species to breakdown chemical toxins and even feed on pathogenic bacteria in the soil. Paul Stamets is a well known mycologist who has pioneered the use of fungi in bioremediation. Bioremediation is the process of using living organisms to decontaminate the environment, for instance after a chemical spill. Mycoremediation refers to bioremediation specifically utilizing fungi.

Here is a link to a short Youtube video explaining mycoremediation by Harvard Museum of Natural History. This video was part of the 2020 Virtual Fungus Fair (uploaded Nov 12 2020):

In his article “Helping the Ecosystem through Mushroom Cultivation” Paul Stamets discusses the broad applications of mycoremediation for neutralizing both bacterial and chemical contaminants:

“In this series of experiments, our group made two other significant discoveries. One involved a mushroom from the old growth forest that produced an army of crystalline entities advancing in front of the growing mycelium, disintegrating when they encountered E. coli, sending a chemical signal back to the mother mycelium that, in turn, generated what appears to be a customized macro-crystal which attracted the motile bacteria by the thousands, summarily stunning them. The advancing mycelium then consumed the E. coli, effectively eliminating them from the environment. The other discovery, which I am not fully privy to, involves the use of one of my strains in the destruction of biological and chemical warfare agents. The research is currently classified by the Defense department as one mushroom species has been found to break down VX, the potent nerve gas agent Saddam Hussein was accused of loading into warheads of missiles during the Gulf War. This discovery is significant, as VX is very difficult to destroy. Our fungus did so in a surprising manner.”

It’s important to note that this research is focused on specific species of mushrooms with specific bacteria or chemicals. Just because you see mushrooms growing somewhere doesn’t mean that soil is safe and free of contaminants. Likewise, mushrooms grown in contaminated soil may or may not be safe for human consumption. It depends on the species, the chemicals and the interactions between the mushrooms and the chemicals they are expected to remediate. When in doubt, avoid eating mushrooms unless you are 100% sure they are safe.

In any case, there is a growing body of research on the applications of mycoremediation, which I find fascinating. In fact, mycoremediation may even have something to offer the victims of the chemical fallout from the East Palestine, Ohio disaster.

The train cars involved in the chemical spill in East Palestine contained vinyl chloride. However, the ill-advised decision to burn the vinyl chloride created the conditions to form dioxin, which is a byproduct of burning chlorinated compounds. Dioxin is extremely persistent in the environment and is considered the most dangerous chemical known to man. According to the following article in Natural News, Paul Stamets was interviewed some years ago about what species of mushroom he would recommend for remediating dioxin contamination. His recommendations included Oyster mushrooms and Turkey Tail mushrooms.

Here is a link to this article: https://www.naturalnews.com/2023-02-28-mushrooms-could-clean-up-dioxin-tainted-east-palestine.html#

Pending the results of independent third party testing, if I personally lived in East Palestine I would have evacuated the town long ago. What remains to be determined is how far from “ground zero” the damage extends since dioxin is hazardous to human and animal health in extremely low quantities. I’ve seen estimates and maps of the projected range of exposure from this fallout that include my area of Virginia. Then again, when my neighbor’s house burned down a few years ago, was that a greater dioxin exposure for me personally? Ultimately testing will need to be done in order to determine the extent of the damage.

In any case, I’m hopeful that mycoremediation may have something to offer for those affected by this manmade disaster. Certainly, I think mycoremediation would be applicable to small garden plots or raised beds which can be easily covered with straw and inoculated with Oyster mushroom spawn. Then next season, once the Oyster mushrooms have done their job, perhaps you could plant vegetables on that plot again (although I would strongly recommend soil testing for dioxin and any other contaminants you are concerned about if that is what you are trying to remediate).

Turkey Tail is the other species of mushroom that Paul Stamets reportedly recommended for dioxin remediation. Turkey Tail naturally grows on fallen or otherwise rotting logs throughout much of North America. But if you haven’t seen any in your neighborhood or you simply want more of it, you can buy Turkey Tail plug spawn (i.e. wooden dowels permeated with Turkey Tail mycelium) and tap them into holes drilled into freshly cut logs or stumps. Some species of mushrooms will only grow on certain species of wood. But Turkey Tail isn’t too particular and is known to colonize over 70 species of hardwoods and even conifers. Here in Virginia we have an abundance of invasive, fast growing Paradise trees which aren’t good for much. The next chance I get I’ll see if I can put some Paradise trees to use growing Turkey Tail.

I haven’t read this nor seen any studies to back it up, but intuitively I would think that your Turkey Tail plug spawn could cover a larger, deeper area for the purpose of remediation if it were strategically inoculated into freshly cut stumps around a property rather than logs left lying on the ground. This is because the stump of a tree is connected to roots that go deep into the soil and spread out. Therefore, when you inoculate the stump with mushroom spawn, it’s a bit like injecting a medication into a circulatory system except that in this case the vessels are tree roots rather than blood vessels. Now the mycelia should be able to spread more quickly over a deeper and wider area than it otherwise could have as it consumes the wood of the tree.

As for large agricultural fields, pastures and whole farms, I’m not sure if inoculating a few stumps with Turkey Tail or making beds of Oyster mushrooms would be sufficient remediation. Then again, mycelia can travel extraordinary distances under the right conditions.

The following is another quote from the above referenced article “Helping the Ecosystem through Mushroom Cultivation” by Paul Stamets regarding the breadth and density of mycelia:

“Covering most all landmasses on the planet are huge masses of fine filaments of living cells from a kingdom barely explored. More than 8 miles of these cells, called mycelia, can permeate a cubic inch of soil. Fungal mats are now known as the largest biological entities on the planet, with some individuals covering more than 20,000 acres. Growing outwards at one quarter to two inches per day, the momentum of mycelial mass from a single mushroom species staggers the imagination. These silent mycelial tsunamis affect all biological systems upon which they are dependent.”

So perhaps there is hope that nature has the built in mechanisms to recover from so grievous an insult. A holistic view of healthcare looks for ways to facilitate the inherent capacity of the body to heal. Holistic medicine sees each person as a whole comprised of body, mind and spirit. If we now apply the same mindset to our environment, we may find that God has already provided the pathways of healing to follow.

I’ll end with a relevant quote from Scripture:

“If my people, which are called by my name, shall humble themselves, and pray, and seek my face, and turn from their wicked ways; then will I hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin, and will heal their land.” (Holy Bible KJV, 2 Chronicles 7:14)

References: (see also in-text links and references)

Benson KF, Stamets P, Davis R, Nally R, Taylor A, Slater S, Jensen GS. The mycelium of the Trametes versicolor (Turkey tail) mushroom and its fermented substrate each show potent and complementary immune activating properties in vitro. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019 Dec 2;19(1):342. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2681-7. PMID: 31791317; PMCID: PMC6889544. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6889544/

Beyer, D. Basic Procedures for Agaricus Mushroom Growing. PennState Extension. Updated Sept 7 2017. https://extension.psu.edu/basic-procedures-for-agaricus-mushroom-growing

Canigueral, D. Shiitake: The Very Common Mushroom in Japanese Cuisine. Sept 16 2022. https://japanesetaste.com/blogs/japanese-taste-blog/shiitake-the-very-common-mushroom-in-japanese-cuisine

Carter, B. MUSHROOMS can help clean up dioxin-tainted East Palestine, Ohio. Natural News. Feb 28 2023. https://www.naturalnews.com/2023-02-28-mushrooms-could-clean-up-dioxin-tainted-east-palestine.html#

Cör D, Knez Ž, Knez Hrnčič M. Antitumour, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Antiacetylcholinesterase Effect of Ganoderma Lucidum Terpenoids and Polysaccharides: A Review. Molecules. 2018 Mar 13;23(3):649. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030649. PMID: 29534044; PMCID: PMC6017764.

Eirdosh, D. “Farmers of Fungi: Growing Mushrooms and Mycorrhizae in Your Vegetable Patch” https://www.homestead.org/gardening/growing-mushrooms-mycorrhizae/

Gong S, Chen C, Zhu J, Qi G, Jiang S. Effects of wine-cap Stropharia cultivation on soil nutrients and bacterial communities in forestlands of northern China. PeerJ. 2018 Oct 9;6:e5741. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5741. PMID: 30324022; PMCID: PMC6183509. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6183509/

Gracian, A. Wine Cap Mushrooms: Boost Your Edible Landscape Beds! AlboPepper https://albopepper.com/wine-cap-mushroom-bed-cultivation-stropharia-rugosoannulata.php

Jiang Q, Zhang M, Mujumdar AS. UV induced conversion during drying of ergosterol to vitamin D in various mushrooms: Effect of different drying conditions. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020 Nov;105:200-210. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.09.011. Epub 2020 Sep 22. PMID: 32982063; PMCID: PMC7508054.

Nutritionvalue.org. Mushrooms, raw oyster, nutrition facts and analysis. Nutrition Facts Exposed. Nutritionvalue.org. 2023. https://www.nutritionvalue.org/Mushrooms%2C_raw%2C_oyster_nutritional_value.html?size=100%20g

Schulzová V, Hajslová J, Peroutka R, Gry J, Andersson HC. Influence of storage and household processing on the agaritine content of the cultivated Agaricus mushroom. Food Addit Contam. 2002 Sep;19(9):853-62. doi: 10.1080/02652030210156340. PMID: 12396396.

Sewak, D. Sewak, K. How to Grow Wine Cap Mushrooms. Mother Earth News. Feb 15 2016. https://www.motherearthnews.com/organic-gardening/how-to-grow-wine-cap-mushrooms-ze0z1602zhou/

Shapiro, C. Ferguson, R. Wortman, C. Maharjan, B. Krienke, B. Nutrient Management Suggestions for Corn. Nebraska Extension. Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. April 2019 https://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/pdf/ec117.pdf

Stamets, P. Helping the Ecosystem Through Mushroom Cultivation. April 20 2020. https://paulstamets.com/mycorestoration/helping-the-ecosystem-through-mushroom-cultivation

The Nutrition Source. Mushrooms. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/food-features/mushrooms/

Disclaimer: The information contained in this newsletter is for educational purposes only. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your personal physician for medical advice. Do not delay treatment based on the information in this newsletter. This is also not dietary advice. Please consult a dietician for dietary advice. Never consume any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. I am not responsible for any deaths, injuries, illnesses or damages related to anything you read in this newsletter.